Born: 1912 Lübeck, Germany

Died: 2004 London, England

Year of Migration to the UK: 1939

Other name/s: Klaus E. Hinrichsen

Biography

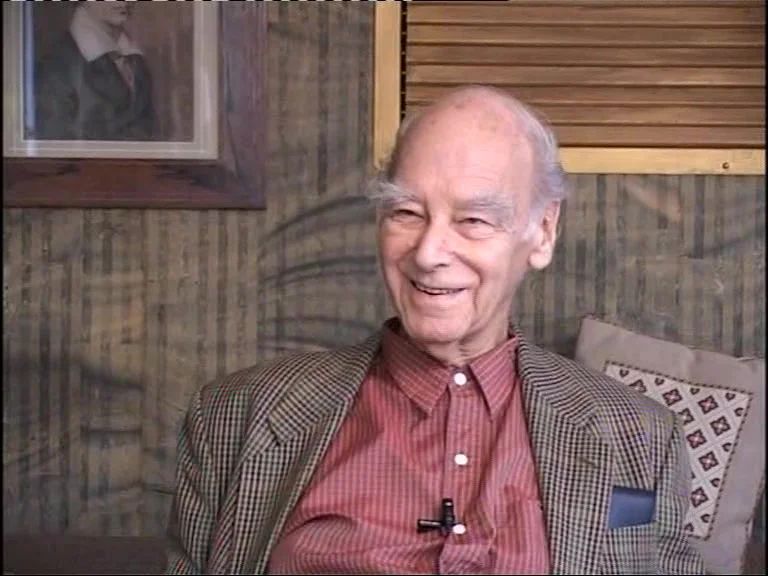

Art historian Klaus Hinrichsen was born in Lübeck, Germany on 19 April 1912. The eldest of four children, he came from an assimilated Lübeck family: his father, Felix, a lawyer, came from Sephardic Jewish ancestors who had left Portugal in the seventeenth century, while his mother, Ida (née Junge), was from north German farming stock. Hinrichsen was raised as a Lutheran Protestant. As a schoolboy, with friends he helped produce the hand-written magazine Das Viereck (The Quadrilateral), which brought him to the attention of the museum director Carl Georg Heise, who encouraged him and involved him in helping to organise exhibitions, largely of German Expressionist art. In 1931 Hinrichsen began studying art history (with theatre history and archaeology) at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München and then moved between universities, including Berlin and Hamburg, as Nazi rule disrupted academic life. In Hamburg he encountered scholars forced out of universities, including Erwin Panofsky, whose lectures he attended in private houses. Hinrichsen completed his doctorate in 1936 on the early Baroque sculptor Tönnies Evers. However, the Nuremberg Laws severely restricted his career prospects. Classified as ‘half-Jewish’, he was barred from museum posts, though he managed to find freelance work writing biographical entries for the prestigious Thieme-Becker artist dictionary. On 9 November 1938 (Kristallnacht), Hinrichsen was arrested by the Gestapo, alongside his father and brother. While his father remained imprisoned, the sons were released due to their ‘half-Aryan’ status. Hinrichsen subsequently used this relative freedom to negotiate with Nazi officials, helping Jewish citizens secure the tax clearances required to emigrate.

Realising his own precarious position, and seeking to avoid impending military conscription, he obtained a three-month permit to visit relatives in England, arriving in May 1939. In London, he managed the British affairs of a Swiss publisher of international medical periodicals. On the eve of war he met his future wife, Margarete ‘Gretel’ Levy, whom he married in 1942. When war broke out that September, he remained in Britain and sent a telegram to his parents claiming he had broken a leg and could not travel. During this time, he volunteered with a Quaker-organised theatrical effort that brought performances to East End factory canteens. Despite being categorised as a low-risk ‘enemy alien’, Hinrichsen was interned for eleven months, from June 1940 to June 1941, at Hutchinson Camp on the Ilse of Man, which became notable for its concentration of artists, scholars and other professionals. Within days he took on organisational responsibilities, serving as secretary and then head of the camp’s Cultural Department and helping develop a programme of lectures, courses, concerts and exhibitions, later nicknamed ‘Hutchinson University’. As Shulamith Behr observes, Hinrichsen framed Hutchinson as ‘a parallel universe, a Greek Menscheninsel, based on education, social harmony and democratic principles’, grounded in Enlightenment notions of Bildung (self-cultivation) and Kultur (Behr 2005, p. 25). He also wrote for the camp newspaper The Camp, contributing criticism and reportage, and recorded the camp’s improvisational art practices, including imagery scratched into blacked-out boarding-house windows with nails and razor blades. He helped facilitate exhibitions, including the second art exhibition on 19 November 1940, which enabled artists to sell work and support welfare funds. During internment he befriended émigré artists, most notably Kurt Schwitters and Erich Kahn; Schwitters painted Hinrichsen’s portrait in the winter of 1940–41 (which later featured in several Ben Uri exhibitions), and a pencil sketch by Kahn of Hinrichsen sculpting (1940–41) survives in the Manx National Heritage collection.

After his release, Hinrichsen remained in Britain, joining the Home Guard and building a successful postwar career in the pharmaceutical and chemicals sector, including founding Millgate Chemicals and later working within networks in the City London. He became a Freeman of the City of London in 1962 and remained active in north London civic life: he chaired the Highgate and Archway Liberal Party for eight years, supported the Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture, helped establish the Jacksons Lane Community Centre (serving as treasurer), and played a leading role in the Highgate Literary and Scientific Institution. Alongside these commitments, he became one of the key chroniclers of artistic life in British internment. His later writings and testimonies synthesised first-hand observation, friendships within the émigré community, and advocacy for artists whose reputations had been disrupted by exile. His chapter ‘Visual Art behind the Wire’, for the book The Internment of Aliens in 20th Century Britain (edited by David Cesarani and Tony Kushner, 1993), became an essential reference for researchers, ranging beyond Hutchinson to other camps in Britain and the Commonwealth and giving due credit to women artists as well. In November 2003 he recorded an extended oral testimony for AJR Refugee Voices. He continued working on projects about internment and artists such as Kahn into his final months. Klaus Hinrichsen died in London, England on 7 September 2004. In the UK public domain, his papers, including camp materials and writings on Schwitters, are preserved in the Tate Archive; related holdings survive in the Manx Museum, and his oral testimony is held in the collection of the Imperial War Museum and is part of the AJR Refugee Voices project.

Related books

- Simon Parkin, ‘Spy School or Technical College? The Mystery of House 36, Hutchinson Square’, in Charmian Brinson and Anna Nyburg eds., Refugees from Nazism to Britain in Trade, Industry, and Engineering (Leiden: Brill, 2025), pp. 166, 168, 171

- Rachel Dickson,’’Our Horizon is the Barbed Wire’: Artistic Life in the British Internment Camps’, in Monica Bohm-Duchen ed., Insiders Outsiders: Refugees from Nazi Europe and Their Contribution to British Visual Culture (London: Lund Humphries, 2019)

- Michael Prodger, ‘The War Art That Came from behind the Barbed Wireì’, Times, 4 March 2019, p. 68

- Jutta Vinzent, Identity and Image: Refugee Artists from Nazi Germany in Britain (1933-1945) (Kromsdorf/Weimar: VDG Verlag, 2006)

- Shulamith Behr, ‘Klaus E. Hinrichsen: The Art Historian behind 'Visual Art behind the Wire'’, in Shulamith Behr and Marian Malet eds., Arts in Exile in Britain 1933-1945. Politics and Cultural Identity (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2005), pp. 17-41

- ‘Klaus Hinrichsen’, AJR Journal, November 2004, p. 15

- ‘Klaus Hinrichsen’, The Times, 1 October 2004, p. 32

- Maxine Seller, We Built up Our Lives: Education and Community among Jewish Refugees Interned by Britain in World War II (Westport: Greenwood Press, 2001), pp. 7, 56, 66, 70, 72, 82, 116, 128, 178, 234

- Ulrike Wendland, 'Biographical handbook of German-Speaking Art Historians in Exile. Life and Work of the Scientists Persecuted and Expelled under National Socialism. Part 1' (Munich: K. KG Saur, 1999)

- Klaus Hinrichsen, ‘Visual Art behind the Wire’, in eds., David Cesarani and Tony Kushner, The Internment of Aliens in 20th Century Britain (London: Frank Cass, 1993)

- ‘Aliens Meet Again’, Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail, 15 May 1990, p. 4

Related organisations

- Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (student)

- Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (student)

- Reallexikon zur Deutschen Kunstgeschichte (contributor)

- University of Hamburg (student)

- University of Rostock (student)

- British Home Guard (volunteer)

Related web links

- Adrian Glew, ‘Klaus Hinrichsen’ obituary, The Guardian, 28 September 2004

- Charlie English, ‘The Island of Extraordinary Captives by Simon Parkin review – Light Amid Darkness’, The Guardian, 26 February 2022

- ‘Hinrichsen, Klaus Ernst’, Oral History, Imperial War Museum

- ‘Klaus Hinrichsen’, AJR Refugee Voices

- Klaus Hinrichsen interviewed by Dr. Anthony Grenville, AJR Refugee Voices Testimony Archive, 20 November 2003

- List of internees of Hutchinson Camp on the Isle of Man

- Jacquie Richardson in conversation with Simon Parkin about her father Klaus Hinrichsen, Insiders Outsiders, 26 Oct 2021

- Naturalisation Certificate, National Archives

- Papers of Klaus Ernst Hinrichsen, Manx Museum

- Papers of Klaus Hinrichsen, Tate Archive

- Portrait of Klaus Hinrichsen by Kurt Schwitters, Hidden Treasures

- ‘Prints Collection of Klaus Hinrichsen to be Auctioned for First Time at Roseberys’, Roseberys, 27 January 2025

- Tate Images

Selected exhibitions

- Forced Journeys: Artists in Exile in Britain c. 1933-45, Ben Uri Gallery and Museum, London and touring (2009-10)