Born: 1901 Christchurch, New Zealand

Died: 1980 Warwick, New York, USA

Year of Migration to the UK: 1926

Other name/s: Leonard Charles Huia Lye

Biography

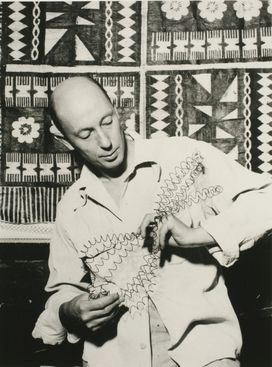

Filmmaker and kinetic sculptor Len Lye was born on 5 July 1901 in Christchurch, New Zealand. After his father’s death, he spent a peripatetic childhood in Wellington and Cape Campbell, where a year living at a lighthouse started his fascination a with light and machinery. Lye studied briefly at Wellington Technical College before travelling through Australia and Samoa in the early 1920s. Fascinated by Pacific and Indigenous art, he became one of the first non-Māori New Zealand artists to actively study and engage with Māori, Aboriginal and Oceanic visual cultures. Expelled from Samoa by the colonial authorities for living in an indigenous community, he returned briefly to Australia, before departing for the UK, where he soon developed an experimental practice in film and kinetic sculpture, mixing Western and non-Western elements.

Lye arrived in London in 1926, having worked his way over as a coal trimmer aboard the steamship Euripides. He initially lodged in Chelsea, where he struggled to find work, but quickly embedded himself in avant-garde circles. He joined the progressive Seven and Five Society of abstract artists in 1928, exhibiting alongside Ben Nicholson, Frances Hodgkins and Barbara Hepworth. Among his early UK works were batiks, stone carvings and abstract constructions using tin, cardboard and wire. These featured in the 1928 Seven and Five exhibition (he showed with them regularly until 1934) at the Beaux Arts Gallery, where his pieces were considered at the forefront of modernity. Particuarly notable were Polynesian Connection and Eve, a vertical tin sculpture, evoking both Māori tiki and Cubist abstraction. During this time, Lye lived on a moored barge in Hammersmith and worked at the nearby Lyric Theatre as a scene-shifter and flyman. Through his connections with sculptor, Eric Kennington, he met Robert Graves and was introduced to the Seizin Press, founded by Graves and Laura Riding. He contributed book designs and drawings to several of their publications, including No Trouble (1930), and his photograms and automatic compositions frequently featured in their collaborative projects. Lye also became active in the London Film Society, persuading them to subsidise the photography for his first film, Tusalava (1929), an abstract animation made from over 4,000 drawings Influenced by Aboriginal and biological forms.

Throughout the 1930s, Lye’s focused on experimental film. In 1933, he made Peanut Vendor, a puppet film sponsored by Sidney Bernstein. Shortly afterwards, he was commissioned by the GPO Film Unit to produce a series of animated advertisements. His 1935 film A Colour Box marked a radical breakthrough in animation: painted directly onto film without a camera, it used vibrant patterns and pulsing rhythms synchronised to Cuban dance music. Subsequent works for the GPO Film Unit included Rainbow Dance (1936), using Gasparcolour to animate the dancer Rupert Doone, and Trade Tattoo (1937), which combined found footage with Technicolor overlays. These films were shown in British cinemas nationwide, bringing avant-garde techniques to popular audiences.

Lye’s involvement with the GPO and Crown Film Units continued into the early 1940s, during which time he created films such as Musical Poster Number One (1940) and Newspaper Train(1942). His work with the Ministry of Information (MOI), while technically propaganda, retained his distinctive approach to colour, sound and movement. He also collaborated with key figures in British film and art worlds, including Humphrey Jennings, with whom he worked on the short film Kaleidoscope (1936). Jennings, a friend and fellow Surrealist, shared Lye’s interest in collage and abstraction. Lye’s inclusion in the landmark 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition at the New Burlington Galleries further embedded him within the British avant-garde. His contributions included photograms, such as Self Planting at Night and Marks and Spencer in a Japanese Garden, as well as the gestural painting Snow Bird (then titled The Jam Session), which drew on his direct film experiments. The following year he showed with the leftwing Artists International Association, (Surrealist section). By the early 1940s, Lye was well established in the London art world. His final years in the UK were spent contributing to wartime film projects before immigrating to the USA in 1944. Though he continued to make films and kinetic sculptures in New York, it was during his two decades in London that Lye developed the core elements of his theory and practice: his belief in ‘pure figures of motion’ and his desire to make art that would affect the viewer physically and emotionally.

Lye returned to New Zealand in 1977 to oversee a major retrospective of his work at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in New Plymouth, and shortly before his death, he established the Len Lye Foundation. Len Lye died in Warwick, New York, USA, on 15 May 1980. In the UK, his work has been revisited in surveys at the Ikon Gallery, Birmingham (2010), and in film retrospectives at the BFI (British Film Institute, London). His works are held in UK public collections, including the BFI and Ikon Gallery, Birmingham.

Related books

- Len Lye and Roger Horrocks, ed., Poems: Len Lye (New Plymouth: Govett-Brewster Art Gallery/Len Lye Foundation, 2021)

- Roger Horrocks, ed., Zizz!: the life and art of Len Lye in his own words (Wellington: Awa Press, 2015)

- Gregory Burke et al., Len Lye: motion sketch, exh. cat. (New York: Drawing Center, 2014)

- Luke Smythe, 'Len Lye: The vital body of cinema', October, No. 144, 2013, pp. 73 -91

- Roger Horrocks, Art the moves: The work of Len Lye (Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2013)

- Desmond O’Rawe, '(Pro) Motion Pictures: Len Lye in the Thirties', Quarterly Review of Film and Video, Vol. 29, No. 1, 2012, pp. 64-75.

- Len Lye and Laura Riding, ed., No Trouble (Majorca: Seizin Press, 1930)

Public collections

Related organisations

- Lyric Theatre (scene-shifter and flyman)

- Seven and Five Art Society (member)

Related web links

- Anne Kirker, 'The Early Years in London', Art New Zealand

- Christchurch Art Gallery

- Harvard Film Archive

- Inga Fraser, 'Colour and Kinesis', Tate Etc., 24 June 2020

- Govett-Brewster Art Gallery | Len Lye Centre

- Museum of New Zealand

- New Zealand History

- Senses of Cinema

- The Len Lye Foundation

Selected exhibitions

- Len Lye: Motion Composer (solo exhibition), Museum Jean Tinguely, Basel (2019)

- Len Lye: The Opera (solo exhibition), University of Auckland, Auckland (2012)

- Len Lye: The Body Electric (solo exhibition), Ikon Gallery (2011)

- Len Lye (solo exhibition), Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney (2001)

- Len Lye: Retrospective, Pompidou Centre, Paris (2000)

- Len Lye: A Personal Mythology, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth (1977)

- Artists International Association Exhibition (Surrealist section), London (1937)

- Seven and Five Society Exhibition, Leicester Galleries, London (1934)

- International Surrealist Exhibition, New Burlington Galleries, London (1936)

- Seven and Five Society Annual Exhibition, Beaux Arts Gallery, London (1928)