Born: 1918 Old Beach, Australia

Died: 1977 London, England

Year of Migration to the UK: 1948

Other name/s: Robert Oliffe Gage Richmond

Biography

Sculptor Oliffe Richmond was born in Old Beach, Tasmania, on 8 November 1919. Between 1937 and 1941, he studied art and applied art at Hobart Technical College, during which time he closely observed the dynamic physicality of human bodies at ballet classes and wrestling matches, insights that would profoundly shape the emphasis on physical form throughout his artistic career. After completing his diploma, he gained practical experience working under Amos Vimpany, Hobart’s leading stonemason, where he developed a strong understanding of materials, carving techniques, and tool handling. He was also influenced by the modernist ideas of the New Zealand-born sculptor, Alison Duff. During the Second World War, he enrolled in the Militia in 1940, before serving in New Guinea with the Royal Australian Engineers.

Following his discharge from the army in 1946, Richmond resumed his artistic training at East Sydney Technical College, in Australia, where he studied sculpture under Lyndon Dadswell. In 1948 he was awarded a New South Wales government travelling scholarship. Formally attached to the Royal College of Art in London, England, Richmond soon ventured across Europe to visit major art centres. On his return to England, he worked as an assistant to the celebrated sculptor Henry Moore between 1949 and 1951, occasionally collaborating on significant pieces. In 1951, Richmond succeeded Moore as a sculpture tutor at Chelsea School of Art.

Richmond’s career flourished throughout the 1950s and 1960s. His work featured in major group exhibitions in London, the UK regions, and internationally — in Paris, Oslo, Zurich, Sydney, Melbourne, and Phoenix, Arizona, USA. His first solo exhibition at London's Molton Gallery (founded by émigré, Annely Juda, in 1960) garnered praise from critic, Edward Lucie-Smith, who remarked on Richmond’s unexpected maturity as an artist (Australian Dictionary of Biography). Further solo shows followed in Belfast and New York (1964), London (1965, at the Hamilton Galleries also founded in 1963 by Juda), Canberra and Melbourne (1967), and Sydney (1968). At his Belfast exhibition in 1964, several notable bronzes were shown, including Twisting Man, praised for its dynamic form; Fallen Wrestler, admired for its dignity and pathos; Rolling Figure, a balletic static study, and Caveat, a group work conveying strong emotional resonance (Belfast Telegraph, 1964). In 1966, Richmond’s Lizard Man and other bronzes were exhibited at the Marjorie Parr Gallery in London, where he was again recognised for his contribution to contemporary sculpture.

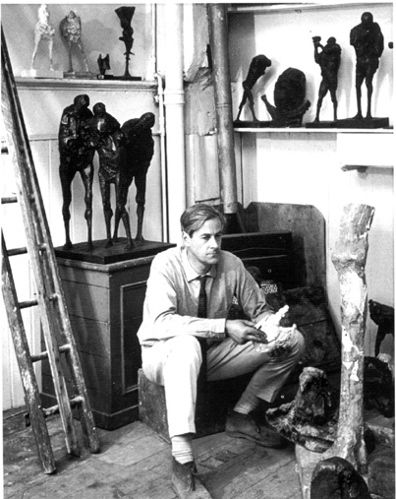

Early in his career, Richmond, who sometimes signed his work with the initials ‘O.R.’, became known for highly textured figurative bronzes, which expressed intense human energy and inner tension. Pieces such as Twisting Man (1960, Arts Council Collection) exemplified his fascination with dynamic forces and latent movement. In 1958 Richmond completed one of his most prominent commissions, Resurrection, a monumental concrete sculpture installed above the west door of Christ Church, Dogsthorpe in Peterborough. The powerful figure, characterised by its massive limbs and dynamic stance, divided opinion among parishioners, but captured Richmond’s distinctive approach to religious imagery. While some found its unfamiliar style controversial, others praised it as ‘tremendously alive — a wonderful symbol of what the sculptor intended to convey’ (Peterborough Standard, 1958). His bronze figures resonated with the British postwar humanist tradition, capturing the stresses and exertions of the human body. However, Richmond’s artistic evolution was marked by continual experimentation. By the late 1960s, he had shifted towards assembling industrial aluminium components into abstract sculptures that maintained subtle human associations, abandoning organic textures, in line with prevailing trends. His later creations included intimate carvings in dense woods such as ebony, and small bronze abstracts, made using the lost-wax casting method, each suggesting monumental scale despite their compact forms. In the 1970s, Richmond produced some of his most dramatic works: towering anthropomorphic structures made of laminated woods and bolted timbers. These massive sculptures, exhibited at the Commonwealth Institute in London in 1976, filled rooms with an imposing presence, evoking comparisons to the fantastical machines of H.G. Wells' War of the Worlds. Critics admired these works for their complexity and commanding scale. Of the 70 works exhibited, 14 were large wooden constructions, 25 were bronzes, and 8 were aluminium pieces, reflecting the breadth of his technical and material experimentation.

Throughout his career, Richmond remained steadfast in his commitment to artistic integrity over commercial success. He found inspiration in ancient sites such as Stonehenge, which reinforced his connection to an enduring sculptural tradition. He lived with his wife in Grayswood, Surrey, before settling in London. Oliffe Richmond died in Kensington, London, England on 26 February 1977. Three of his sculptures were exhibited posthumously in the Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition in the same year. In the UK public domain, his work is represented in the Arts Council Collection and Tate Collection.

Irene Iacono

Related books

- Jane Eckett, ‘Progression in Space: Works From The Norma Redpath Studio’, essay accompanying studio sale of the late Norma Redpath, sculptor, held at the Charles Nodrum Gallery, July 2013

- Eileen Brooker, 'Eileen and Oliffe: Letters of a Lifetime' (Tasmania: Midway Point, 2006)

- ‘Sculptures in Wood’, Fulham Chronicle, 13 February 1976, p. 17

- ‘Over 70 Works in Art Show’, Wolverhampton Express and Star, 2 February 1976, p. 23

- ‘Small Sculptures and Drawings’, Kensington Post, 11 February 1966, p. 4

- ‘An Arresting Exhibition of Sculpture’, Belfast Telegraph, 8 May 1964, p. 16

- ‘Sculptor’s Works Here’, Belfast News-Letter, 21 April 1964, p. 1

- ‘Resurrection Statue ‘Makes Christ Church Look Like Wrestling Booth’’, Peterborough Standard, 11 July 1958, p. 1

- ‘Leamington Open Air Exhibiton’, Birmingham Daily Post, 2 June 1958, p. 16

- ‘Spreading a Little Colour’, Birmingham Daily Post, 7 October 1957, p. 28

Public collections

Related organisations

- Chelsea School of Art (teacher)

- East Sydney Technical College (student)

- Hobart Technical College (student)

- Royal College of Art (student)

Related web links

- 1965 exhibition, Hamilton Galleries

- Australian Dictionary of National Biography

- Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies

- Ocula Magazine

- Robin Gibson Gallery

- Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition, 1977

- Sculpture online

- Sculpture Sphinx by Oliffe Richmond, Art Gallery New South Wales

Selected exhibitions

- Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition, Burlington House, London (1977)

- Prints for Presentes including Oliffe Richmond and David Gentleman, Curwen Gallery, London (1966)

- Oliffe Richmond: Recent Sculpture, Hamilton Galleries, London (1965)

- Oliffe Richmond: Sculpture Drawings, New Gallery, Belfast, Northern Ireland (1964)

- Sculpture Exhibition, Battersea Park, London (1963)

- Group exhibition, Hamilton Galleries, London (1963)

- Solo exhibition, Molton Gallery, London (1962)

- Contemporary Sculpture and Sculptors’ Drawings, organised by the Arts Council, Herbert Art Gallery, Coventry (1962)

- Open Air Exhibition, Leamington Spa, Warwickshire (1958)

Ben Uri archive

Consult items in the Ben Uri archive related to [Oliffe Richmond]

Ben Uri library

Publications related to [Oliffe Richmond] in the Ben Uri Library