Born: 1911 Paris, France

Died: 1944 Moffat, Scotland

Year of Migration to the UK: 1914

Other name/s: Sylvain Klusko

Biography

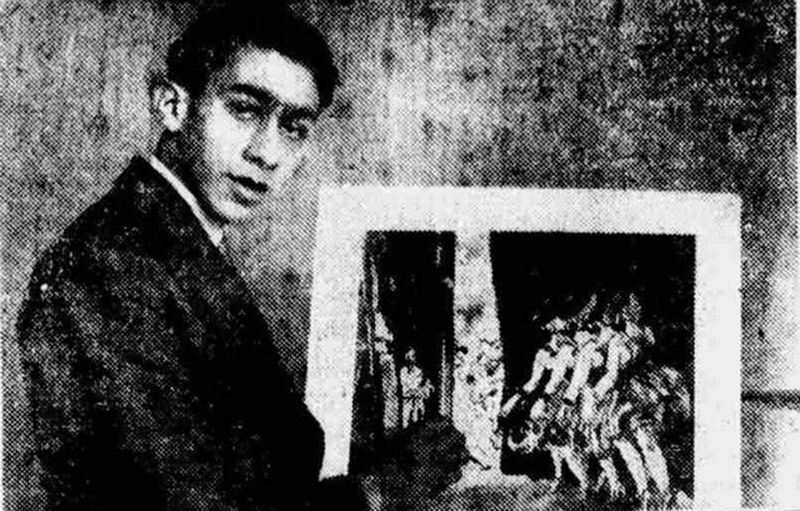

Painter Sylvain Kluska was born on 17 April 1911 in Paris, France, to Jewish parents of Polish and Romanian origin. In 1914, his family moved to London, settling in the working-class neighbourhood of Whitechapel in the East End. His father, a tailor, had come to England seeking better prospects. From a young age, Kluska demonstrated extraordinary artistic talent. By the age of three, he was producing whimsical pen-and-ink sketches that surprised his parents, and by seven, he was already inseparable from his paint box.

Kluska was educated at the Davenant Foundation Grammar School and went on to study at St. Martin’s School of Art on a scholarship. It was here that he began to depict the urban landscape that surrounded him with meticulous detail and sensitivity. At just fourteen, he first exhibited at the Whitechapel Art Gallery with a painting of the ‘pathetically ugly roof-tops’ he saw from his bedroom window. Reflecting on this subject, he remarked: ‘Don’t think I specialise in rooftops, but I have lived amongst them so long that it is not surprising that I see more in them than most people’ (London Daily Chronicle 1929). A year later, at fifteen, he participated in a children’s art exhibition at the same gallery. By seventeen, he had achieved national recognition: two of his watercolours, Soho Roof Tops and Odds and Ends, were accepted into the 1929 Royal Academy Summer Exhibition. This made him the youngest exhibitor that year, a fact widely reported in the British press and internationally by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency and Associated Press. Soho Roof Tops displayed extraordinary attention to detail — 900 bricks painted individually over 14 days — while Odds and Ends was a tiny, intricate sketch of the cluttered backyards behind his East End home. He subsequently showed in the Summer Exhibition in 1931 and 1936.

Kluska's early ambition was to gain entrance to the Royal College of Art (RCA), a goal he achieved when he won an L.C.C. scholarship shortly after his Royal Academy debut. He later earned a second scholarship for advanced study. His time at the RCA was marked by both creative growth and controversy. In 1932, he made headlines again for publicly challenging Sir William Rothenstein, the RCA Principal, during a speech at the Victoria and Albert Museum. Disputing Rothenstein’s teaching methods and accusing him of promoting a rigid approach to art education, Kluska was hurried out of the hall by friends. The incident highlighted both his passion for artistic freedom and his refusal to conform. Despite this outburst, Kluska continued to secure prominent exhibitions. In 1931, his watercolour A Back-Room View was shown again at the Royal Academy and purchased by the Marchioness of Bute, an aristocratic endorsement that solidified his rising status in elite art circles. The same year, he began exhibiting regularly at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, in the inaugural East End Academy exhibition in 1932. His submissions included the pastel Job and his Comforters and a tempera work titled East End Street Scene. These pieces were praised for their strong connection to place and community, emblematic of the East End’s Jewish working-class milieu. His pastel was singled out in a review as ‘one of the most remarkable things in the exhibition’ (Truth, 2 November 1932, p. 19). Throughout the 1930s, Kluska pursued a dual career as a fine artist and commercial illustrator. He worked freelance, contributing humorous sketches and cartoons to newspapers and creating illustrations for advertisers. His interest in aviation led him to draw aircraft, some of which were published in the journal Flight. He later formed a commercial design partnership under the name ‘Kluska & Coleman’, based in Upper Thames Street, and took a position in the Process Department of the London News-Chronicle, where he applied his talents as an illustrator.

Kluska's work, though often rooted in the everyday environment of the East End, demonstrated a philosophical depth. As a young man, he even authored a manuscript in rebuttal to Tolstoy’s What is Art?, stating boldly that he disagreed with the Russian writer’s conclusions. He also dabbled in mechanical invention, designing both a coin-operated cigarette dispenser and a fog-prevention system for railways — both of which, though never commercialised, underscored his inventive mind (London Daily Chronicle 1929). When the Second World War broke out, Kluska enlisted first with the Home Guard and then joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve. He trained as a pilot and was assigned to No. 527 Squadron RAF, a unit tasked with radar calibration. Despite the demands of military service, he continued to sketch, delighting children with his drawings of aircraft during downtime. Tragically, Sylvain Kluska was killed in Moffat, Scotland on 9 May 1944, when his Bristol Blenheim Mk IV aircraft crashed into high ground due to poor visibility. He was 33 years old. Kluska was buried in Willesden Jewish Cemetery in London. His work is not currently represented in the UK public domain.

Irene Iacono

Related books

- In Memoriam, Jewish Chronicle, 7 May 1948, p. 3.

- ‘London Day by Day’, Belfast Telegraph, 3 October 1938, p. 8

- ‘How Artists See The East End Exhibition At Whitechapel’, East End News and London Shipping Chronicle, 28 October 1932, p. 4

- ‘An Unusual Art Exhibition’, Civil & Military Gazette,18 November 1932, p. 3

- ‘Outburst by Art Student’, Daily News (London), 28 November 1932, p. 1

- ‘Art’, Truth, 2 November 1932, p. 19

- ‘Academy Exhibition’, Hull Daily Mail, 2 May 1931, p. 7

- C.W.L., ‘Royal Academy’, Gloucestershire Echo, 4 May 1929, p. 2

- ‘Boy Artist’s Two Pictures at R.A.’, London Daily Chronicle, 30 April 1929, p. 3

- ‘London Boy Artist's Success at the Royal Academy’, ‘Evening News, 30 April 1929, p. 1

Related organisations

- St. Martin’s School of Art (student)

- Royal Academy of Arts (exhibitor)

- Royal College of Art (student)

Related web links

- Naturalisation certificate, London Gazette

- Royal Academy of Arts online catalogue

- Stephen Oryszczuk, 'Using Lockdown to Research and Archive the Jewish Heroes of the RAF', Jewish News, 12 June 2020

- Warrant Officer Sylvain KLUSKA

Selected exhibitions

- Royal Academy Summer Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts (1936, 1931, 1929)

- East End Academy, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London (1932)

- Children’s Art Exhibition, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London (1926)

- Whitechapel Art Gallery, London (1925)

Ben Uri archive

Consult items in the Ben Uri archive related to [Sylvain Kluska]

Ben Uri library

Publications related to [Sylvain Kluska] in the Ben Uri Library